MARTIN, Maria

Ballarat's 'stubborn' survivor A Different time and place: From Italy to Australia, via Hell

Maria Martin is slightly bemused about the tattoos her grandchildren have chosen. It's not a generational dispute over getting ink: Martin has a tattoo of her own. She cannot fathom why they choose to copy the one she bears. Perhaps it is because, unlike her grandchildren, Maria Martin had no choice in being tattooed. Now blurred almost beyond deciphering, the numbers 82617 are inked on the thin skin of her left forearm, just below her elbow, slightly over one inch long. The position of the tattoo is a familiar one. May victims who survived the Holocaust, those who had been at the Auschwitz concentration camp, bore one in the same place.

Maria Bezin is born on the 7th of December 1919 just prior to the rise of Mussolini and his Partito Nazionale Fascista, the National Fascist Party. In childhood, she is perhaps blissfully unaware of what is happening around her. As a young woman, this ignorance evaporates. The approaching war and the fascists' determination to install, by any means, a sense of national pride sees Slovenians and other 'non-Italians' attacked. Her carefree days disappear.

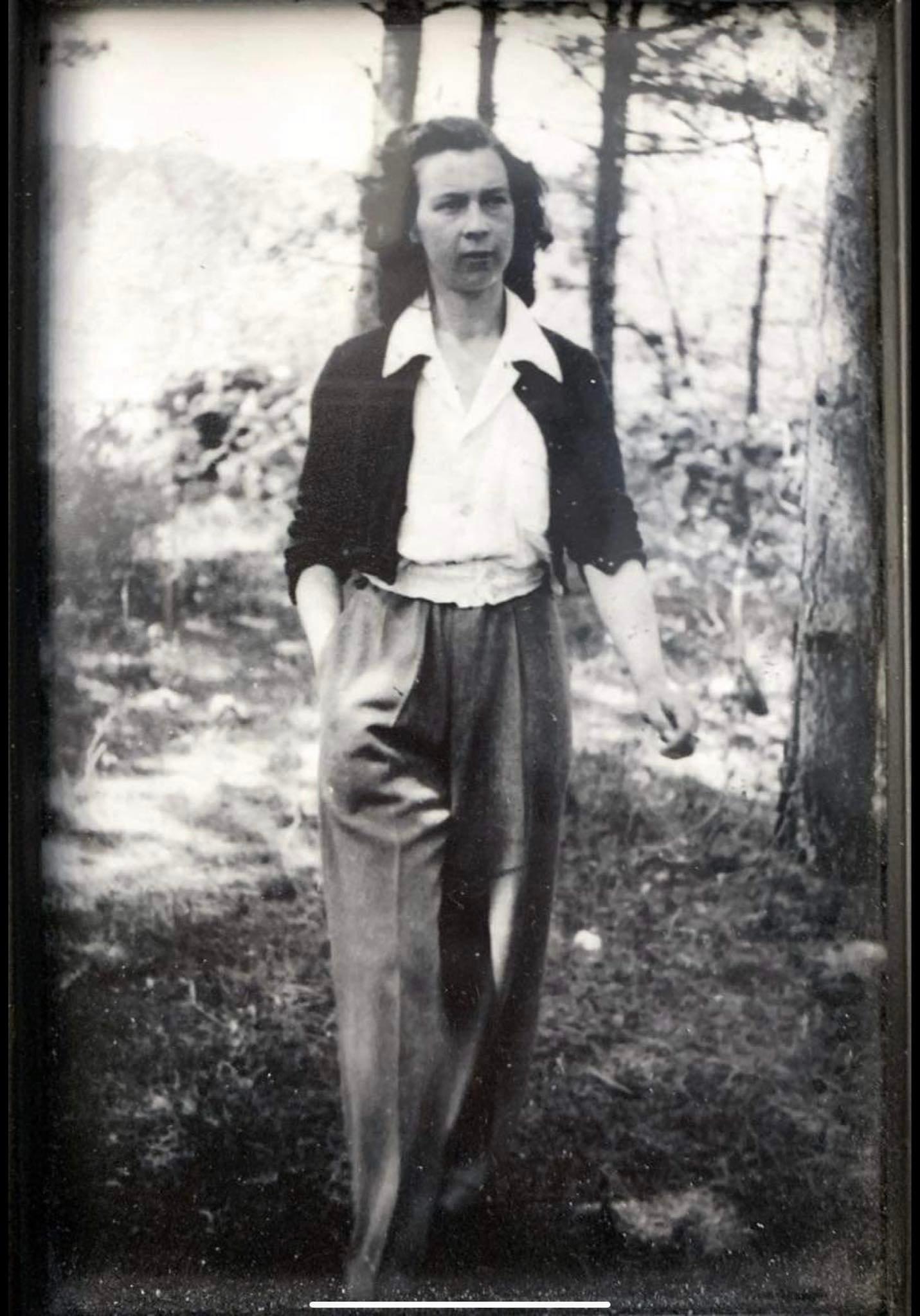

In early 1944, 23-year-old Roman Catholic Maria Bezin is sent from her northern Italian hometown of Prosecco near Trieste - or in Slovenian, Trst - on the Adriatic Sea, to the Nazi camp in the annexed Polish territories.

Maria is one of seven children, Bezin's mother dies when she is nine. Her father dies in the year before she was sent to the concentration camps. She is grateful he didn't live to see the suffering she would endure.

Now known widely as the name of a variety of Italian sparkling wine, before World War II Prosecco is a village outside of the newly annexed and cosmopolitan city of Trieste. As a child and as part of her community, Maria speaks Slovenian. National identity as we understand it today was not as strictly defined 100 years ago; people are likely to identify with a region or town as they are a country. Prosecco, today a suburb of Trieste, borders what was then the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and the Kingdom of Austria-Hungary in an area known as the Julian March by Italians, Istria by Croatians, and the Slovene Littoral by Slovenes.

Her crime is to have been accused of supporting her brothers hiding in the nearby Dolomite Mountains, who are fighting with the Resistance as partisans against the German Wehrmacht. Arrested and transported in the space of 24 hours, Bezin cannot fully comprehend what is taking place; what indescribably awful change is coming. She was beaten, smacked, punched, and put in jail for one night before being transported to Germany. Just like that on a train. Given just enough time to pack a bag, the 23-year-old puts in her treasured belongings, her jewelry, and her best clothes; she wears her best suit. Martin thinks, perhaps this will be like a holiday. The truth of what is happening in Eastern Europe, that mass murder is taking place at an ever-increasing rate as the Allied forces close in on the failing Nazi regime, is unknown to any but those trapped in the camps. To Maria, it looked like a labor camp but it wasn't long before she worked out what it was, because they burnt people !!! Taken to the railway station in Trieste with other prisoners, Maria discovered her careful packing and wearing her best clothes is in vain. Even less so: it is devastatingly ironic in the blackest way. There are no first, second, or third-class carriages waiting at the platform. There is no platform. There is no food or water. There are goods wagons, and the guards jam prisoners into them as tightly as possible, like livestock. Their horrific journey begins; people die in a week of exhaustion, thirst, and suffocation. When people died in the other wagons they threw them out.

Maria readily admits she took food to the fighters, who had established a sophisticated network of supply and command lines among the pines and the thickly-planted understory of oak, ash, and maple forests. Their works included a hospital dug into the limestone caves of the mountainside.

Once at Auschwitz, the mix of nationalities, and how they are treated, is a shocking revelation. Maria has no memory of any kindness in Auschwitz, of any person showing any glimpse of humanity to the prisoners. It was a world of unrelenting brutality. The guards within the camp are mostly forced laborers from annexed states. The conditions induce illnesses that kill many inmates. Maria contracts typhus and dysentery; she is still moved to the Ravensbruck camp to work in munitions. She gets sicker; the Germans determine she will go to Bergen-Belsen, a camp for with designated areas for women and for 'recovery' from sickness. En route, her transport train is attacked by Allied aircraft and destroyed. The survivors of the attack are forced to walk to Belsen; those who fail are set upon and savaged by guard dogs. Maria to this day still would get upset at the sound of a dog chasing a chicken in her backyard.

Auschwitz was very, very bad but when we came to Bergen-Belsen, it was depressing. I felt like I would never come home anymore, because in front of the barracks were dead people, just lying on the floor. Because of the German accuracy in documentation, it is possible to account for where Maria Martin had been moved to. She is desperately unwell and is assigned to a barracks full of sick and dying prisoners. But she is so cold when she began to walk to her barracks in the night, so she went back to her previous barracks as it was slightly warmer with more inmates. The next day, all the inmates of the barracks she was meant to have gone into are gassed. Shortly after, the German desire for organized genocide is abandoned in the Allied advance, and Maria Marin is left, alone.

Maria Martin believes dreams have consequences and applications in daily life. She tells of one dream which she had just prior to liberation. "One morning I woke up in Belsen, and I knew we were going to be liberated, because my father came (in the dream) and he took me up a hill and he said, 'Look around us, it's nice and clear.' "I'm tired Daddy. I can't walk anymore." "No keep going, keep going; you'll be happy."

"I was positive I dreamed about my father, and change was going to come, and two days later the Red Cross came. The dream came true. I told it to (her daughter) Cynthia when she was grown up, I told her it was a funny story because it was really true."

Bergen-Belsen was liberated on the 5th of April 1945 by British and Canadian soldiers, who were confronted not only by the horrors of the dead and those about to die but by the threat of a typhus outbreak. Australian journalist Ronald Monson went into the camp with a medical team. The liberation was Red Cross. Maria recalls the young Australian journalist who came in with the Red Cross and he was taking photos. Monson, 40, is so distraught at what he sees, he punches and flattens the first German he meets.

Maria is taken to the barracks that have now been turned into a hospital. She does not remember how long she was there but was very thin. Because she needed medical treatment she is taken to a private house and was treated very well. She went home almost after the finish of the war. And back home, her sister and all the neighborhood, thought she was dead because she didn't come straight home. She was 36 kilos when she was liberated, all bones and she had been away from home for twelve months.

After liberation and recuperation, Maria is taken to a storage area where the Germans have stockpiled belongings taken from the inmates. She sees jewelry, expensive artwork, and fine goods and is told to take what she wants. Instead, she chose a simple oil painting, a landscape in a cheap frame. For someone to carry this all this way, it meant something to them, it was important to them.

Maria Bezin now Martin following her marriage to a French-Italian fellow villager, Edimiro, arrived in Australia in 1954 aboard the Castel Verde (The Green Castle), docking in Fremantle and Port Melbourne. They are taken by train to the Bonegilla Migrant Reception and Training Centre in northeast Victoria. Maria's husband was not happy at the Centre, she recalls him saying I did not come to Australia to finish in the desert. After a while, they received letters from friends in Melbourne saying to leave everything in Bonegilla and come to Melbourne. They moved to Melbourne and lived in Richmond for a time before moving to Regent. Martin's husband had been a police officer in Prosecco; in Australia, he worked at the Government Aircraft Factories in Fishermans Bend. Maria gained work at Fishermans Bend for General Motors.

Women prisoners in the concentration camps are medicated to cease their menstrual cycles, a practice thought to have rendered many infertile. The couple wanted a child, but think Maria might not be unable to bear children because of her experiences. So they plan to make their fortune in Australia and then return to Trieste, to family. Instead, to their immense pleasure, Maria falls pregnant and a daughter, Cynthia is born in 1955.

The family moved from Regent to Ringwood where they lived for 20 years then eventually moved to Frankston which is where they were living at the time of Edimiro's death. On Tuesday 26th November 2019, 100-year-old Maria Martin met the Governor of Victoria the Honourable Linda Dessau AC to recognise her birthday. She was very pleased about it but said they would be pleased to meet her.

Maria lived with her daughter Cynthia and her family after a move to Ballarat. She died peacefully surrounded by her family on the 24th of July 2021 and is buried with her beloved Edimiro at the Ballarat New Cemetery, Private H Section 1 Row 1 Grave 4.

Thank you to Cynthia Hills and the Ballarat Courier for these beautiful words and an amazing story.